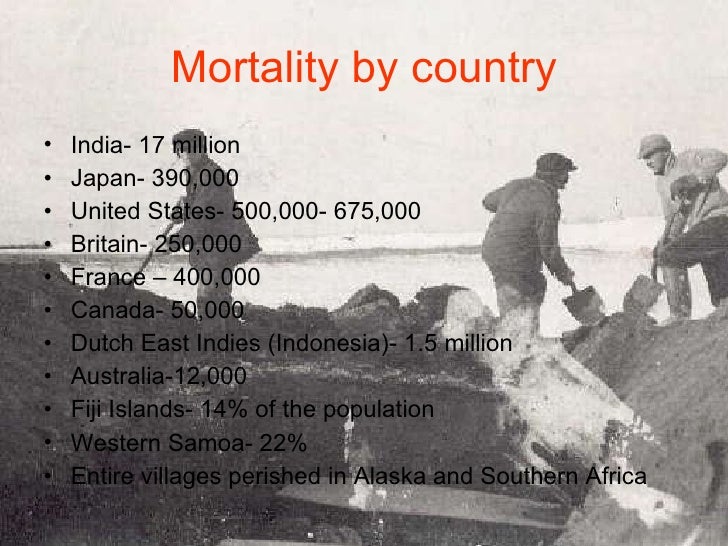

The influenza pandemic of 1918-1919 killed more people than the Great War, known today as World War I (WWI), at somewhere between 20 and 40 million people. It has been cited as the most devastating epidemic in recorded world history. More people died of influenza in a single year than in four-years of the Black Death Bubonic Plague from 1347 to 1351. Known as "Spanish Flu" or "La Grippe" the influenza of 1918-1919 was a global disaster.

It was characterised by high infectivity and unusually high mortality in young people. The virus arrived in Australia in late 1918, and while it seems Australia experienced a milder strain than Europe and the Americas, our hospitals rapidly reached capacity. The emergency prompted the use of the Royal Exhibition Building as a hospital between February and August 1919. “More and more people were getting sick and there was just nowhere to put them,” notes Senior Curator of Public Life and Institutions, Dr Charlotte Smith.

Charlotte curates the Royal Exhibition Building collection, some 5,200 objects and 6,045 archives preserved from the building’s colourful history. There are just two objects in the collection used during the flu era: a pair of medical scissors that were found beneath the floorboards and a hospital stretcher. Photographs from 1919 show the five hundred hospital beds that were set up inside the building. Charlotte notes that “4,046 people were treated in six months, and 392 died. This was a fairly good survival rate compared to other institutions at the time.”

Around 12,500 Australians died during the pandemic. The loss experienced by a community recovering from the horrors of WWI is unimaginable. However, for the newly-founded Commonwealth Serum Laboratories (CSL), it provided a huge burst of public support and recognition which facilitated CSL’s development, expansion, and success.

CSL was established during WWI to respond to Australia’s need for vaccines, serums and anti-toxins, all of which were imported. The war limited the availability of manufactured medicines and facilities for shipping them. Australia was feeling its isolation acutely; clearly, independent production was vital to ensure public health needs could be met.

Almost immediately after opening in 1918, CSL poured all its efforts into battling the coming onslaught of Spanish flu. By March 1919, CSL had packed and produced three million doses of flu vaccine. While accounts of its efficacy suggest that it did somehow reduce mortality, the vaccine was actually derived from a mix of bacterial strains, reflecting the mistaken belief that influenza was caused by a bacterium.

In 1918, the cause of human influenza and its links to avian and swine influenza were unknown. Despite clinical and epidemiologic similarities to influenza pandemics of 1889, 1847, and even earlier, many questioned whether such an explosively fatal disease could be influenza at all. That question did not begin to be resolved until the 1930s, when closely related influenza viruses (now known to be H1N1 viruses) were isolated, first from pigs and shortly thereafter from humans. Examination of mortality data from the 1920s suggests that within a few years after 1918, influenza epidemics had settled into a pattern of annual epidemicity associated with strain drifting and substantially lowered death rates. Did some critical viral genetic event produce a 1918 virus of remarkable pathogenicity and then another critical genetic event occur soon after the 1918 pandemic to produce an attenuated H1N1 virus?

Note: There are three types of influenza viruses (A, B & C). When we’re talking about H1N1, H2N3, and H7N9, we are talking about the influenza A virus – an RNA virus of the orthomyxoviridae (influenza virus) family that is able to infect birds, pigs, and humans, amongst other animals. Variants of the virus that are endemic in birds are called avian influenza; variants that are endemic in pigs are called swine influenza.

In the naming of the subtypes of influenza A virus, ‘H’ stands for hemagglutinin, and ‘N’ for neuraminidase, both of which are antigens embedded on the lipid envelope surface of influenza A virus particles. HA is a protein that mediates binding of the virion to, and entry of the viral genome into, the host cell, while NA is involved in the release of new influenza virions from infected cells.

Patients with the influenza disease of the epidemic were generally characterised by common complaints associated with the flu. They had body aches, muscle and joint pain, headache, a sore throat and an unproductive cough with occasionally harsh breathing. The most common sign of infection was the fever, which ranged from 38-40 degrees Celsius and lasted for a few days.

The onset of the epidemic influenza was peculiarly sudden, as people were struck down with dizziness, weakness and pain. After the disease was established the mucous membranes became reddened with sneezing. In some cases there was a haemorrhage of the mucous membranes of the nose and bloody noses were commonly seen. Vomiting occurred on occasion, and also sometimes diarrhea but more commonly there was constipation. A few physicians associated psychoses with influenza infection.

One article says that "the frequency of mental disturbances accompanying the acute illness in the epidemic has been the subject of frequent comment," The danger of an influenza infection was its tendency to progress into the often fatal secondary bacterial infection of pneumonia. In the patients that did not rapidly recover after three or four days of fever, there is an "irregular pyrexia" due to bronchitis or bronchopneumonia.

The pneumonia would often appear after a period of normal temperature with a sharp spike and expectorant of bright red blood. The lobes of the lung became speckled with "pneumonic consolidations." The fatal cases developed toxaemia and vasomotor depression. It was this tendency for secondary complications that made this influenza infection so deadly.

A skipping rhyme about the 1918 H1N1 flu pandemic

Taken from Virus.stanford.edu. (2016). The 1918 Influenza Pandemic: Responses. [online] Available at: https://virus.stanford.edu/uda/fluscimed.html [Accessed 1 Jul. 2016].

This guide was prepared by Salam Caldis and Sue Patterson of Marymede College in Melbourne. Recreated here with permission and gratitude by Angus Pearson 2018.

The influenza epidemic, known as the "Spanish Flu" of 1918-19 caused nearly 12,000 deaths in Australia and caused many disruptions to community life. It was probably brought to Australia by soldiers returning from World War One, and first appeared in Melbourne in January 1919. The following extracts list a few of the flu reports in south-western Victoria.

21/1/1919

29/1/1919

29/1/1919

2/2/1919 & 3/2/1919 (P2C7 & (P3C2)

3/2/1919 (P3C2)

5/2/1919 (P3C1)

7/2/1919

10/2/1919

12/2/1919

14/2/1919

19/2/1919

26/2/1919

11/4/1919

28/4/1919

30/4/1919

2/5/1919

5/5/1919

9/5/1919

30/5/1919

2/6/1919

9/6/1919

5/5/1919

8/5/1919

12/5/1919

With the outbreak of Spanish Influenza in Melbourne in December 1918, people were advised not to panic. Earlier, local authorities were aware of the disease in Europe and its devastating effects upon the population so strict procedures had been put in place in order to limit its impact. As a consequence Melbourne escaped relatively lightly compared to the number of deaths in Europe and America. Although named ‘Spanish Influenza’ its origin was not in Spain but in United States of America. Eventually it moved to the general population and spread throughout the world.

The disease struck with amazing speed, overwhelming the body’s natural defences, causing uncontrollable hemorrhaging that filled the lungs, resulting in the victim drowning in his or her own body fluids. Individuals who were healthy in the morning were dead in the evening. Not only was it strikingly virulent, it attacked the young healthy adults rather than, as might be expected, the very young, the very old and the infirm. This was a reversal of the normal mortality pattern.

While the Melbourne Argus, in November 1918, was tracking the progress of the disease and resulting deaths in Sydney, no similar outbreak was evident in Melbourne. Nevertheless people were being advised to take precautions. Dr William McClelland, the medical officer for Brighton, proposed in early December to establish an auxiliary hospital in the Wilson Recreation Hall, with one ward each for males and females. By February 22, 1919 the hospital was established and Nurse Powell was appointed as matron to be assisted by VAD nurses.

It was in January 1919 that Victoria was declared infected and the State placed in quarantine with theatres and schools forced to close. The outbreak was first recognised on January 21, 1919.

People were encouraged to wear masks in shops, hotels, churches and public transport. Public meetings of twenty or more people were prohibited and travel in long distance trains was restricted. The New South Wales government closed the border with Victoria prohibiting traffic between the states. Where a member of a family was infected, the house was isolated and quarantine rules were applied.

Local doctors implemented a program of inoculation at local centres with several hundred people taking advantage of this service. Nevertheless there was not universal acceptance amongst members of the community of inoculation as a means of preventing infection or restricting the progress of the disease.

Nurses with children outside the Exhibition Building during the Spanish flu pandemic, 1919.

http://www.auspostalhistory.com/articles/1123.php