Family life and growing up was very different to today. The average size of a family was very large and the poor were very cramped due to the size of their houses. Children didn’t have much time to be kids as when they reached the age of twelve they would work.

The word ‘teenager’ didn’t exist as children didn’t have that transition from child to adult like we do today. When families could no longer send children to school they would send them to work or look after other siblings and the house. The lack of education and a sense of discipline often resulted in ending up in gangs and violence. Poor children attended local public schools until their parents couldn’t pay the fees and were expected to then work, in some cases children younger than seven had to work and provide and income. In the slums the children’s backyard was their alley way, this was very dirty and unsanitary, most children wouldn’t feel lonely as all the children in the community played together.

Children made their own fun with things that didn’t require much equipment. On the contrary rich children could play in backyards however they were forbidden from playing with the poor in the streets. There gardens/backyards were away from the unsanitary surrounding and didn’t have to start working at such young ages, their houses weren’t cramped, they were more educated, and food was more abundant, families also had more time for leisure participating in sports typically reserved for the rich. Living conditions changed quite drastically compared to before the 1920’s meaning that youths were able to participate in new activities like listening to the radio and going to cinemas.

Girls were able to have more freedom in their clothing choices, being able to show more skin, wear makeup and go to the beach with boys in their bathers. Public events became increasingly popular and rich and poor began to mix together more than ever, creating a much less visible barrier. Although times had changed girls were still less adventurous due to the stereotype placed upon them.

Taken from Nickolaou, A. (2016). House and Living Conditions Richmond - Melbourne 1900-1920's.

Housing for the poor is dramatically different to housing for the rich. In the 1900 – 1920’s the positioning of your house practically showed your social status. The rich lived at the top of the hill were it was rarely flooded and away from factories pollution and the poor lived at the bottom of the hill in the ‘slums’ were they were regularly flooded and surrounded in pollution and diseases, the bottom of the hill was un sanitary and not safe and the houses were usually too small for those living in them.

Houses were mostly prefabricated iron houses that were shipped from overseas. These houses were designed for people with near to no skills. Iron houses were extremely cold during the winter and extremely hot in the summer, however they provided somewhat adequate shelter for thousands. Families were squeezed into tiny houses near factories were they worked; people living in the slums generally struggled to pay rent and other necessities.

When the world went through the industrial revolution factories and mass production was introduced, this meant that jobs were produced however resulted in pay being very low making it hard for families to pay for living expenses. Many houses provided shelter for more than 10 people, in houses that had only 2 rooms! Family sizes were extremely large due to the lack of contraceptives. All the above aspects made the quality of life low and also brought the house prices down dramatically.

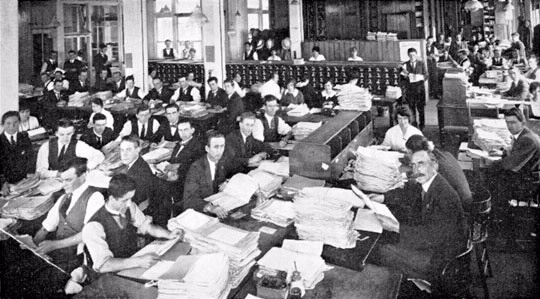

The working life for the poor was considerably harder as many poor families did not have enough money for food and rent as the factories often didn’t pay well. This was the opposite for rich families as they didn’t have to work as hard for little pay. Women in the lower class would usually work at the factories however this was completely opposite for the higher classes. The rich and poor very rarely worked together and had completely different occupations. The rich would usually receive tertiary education enabling them to get higher class jobs such as doctors. The poor on the other hand wouldn’t get education higher than primary education and generally work in factories. The rich worked in town whereas the poor worked in the slums. For a long time there was no real contact between the rich and poor as they were forced to lead completely separate lives.

Average weekly wage in 1901 for males: $4.35 for working almost 50 hours à after inflation this equates to $217.50

This statistic shows the difficulty in affording just the daily essentials.

Taken from Nickolaou, A. (2016). House and Living Conditions Richmond - Melbourne 1900-1920's

A popular form of deception and stand over favoured by crime gangs of the era was using female decoys to lure cashed up, married, men from racetracks and other events, to motel rooms. Here the kissing and cuddling would start in earnest, then one of Taylor’s henchmen would break in on the canoodling couple. Pretending to be the husband of the woman in-flagrante, the stand over began, as the “aggrieved” partner promptly demanded payment from the adulterous man in return for silence around his misconduct. Refusal brought forth the utterance of “Mr Taylor” and this usually made victims offer up cash hand over fist. Terror was an essential element for this blackmail and stand over to work. Two decades later a lesser known figure in the annals Australian crime, Jean Lee (the last women to suffer capital punishment in Australia), used an identical technique to make her ends meet, which ultimately took her to the hangman’s noose.

Taken from Troublemag.com. (2015). STRALIAN STORIES: Snow Business – the thrills and kills of Squizzy Taylor | troublemag. [online] Available at: http://www.troublemag.com/stralian-stories-snow-business-the-thrills-and-kills-of-squizzy-taylor/ [Accessed 9 Jul. 2016].

The tragedies and heroics of self-styled gangsters, including Squizzy Taylor, Long Harry Slater, and Henry Stokes, colour our imaginings of inter-war Melbourne. Speaking to the Victorian Legislative Council in 1924, Sir Arthur Robinson, who had recently left the position of attorney-general, reminded fellow parliamentarians of a terrible ‘crime epidemic.’ He announced that ‘the underworld has reared its head in an unmistakable way, more than ever before in my recollection in the history of this community.’ Yet despite Sir Arthur’s assertion, the most obvious characteristic of most common crimes in 1920s Melbourne is that they all but vanished. In the whole of Victoria offences against the person fell from 3.7 per thousand head of population in 1890 to 0.9 in 1929. By 1931 the rate had fallen further to 0.8. A visitor who had seen Melbourne in the wild days of the 1880s land. Most startling of all was the decline in drunkenness. Measured again in relation to population, alcohol-related offences fell rapidly from the last quarter of the nineteenth century onwards. The men and women of 1920s Melbourne lived far more abstemiously than their parents or grandparents boom, and who returned in the 1920s, would have been immediately struck by this new sense of public order. This fall in crime could, at least in part, be traced to the introduction of early closing of hotels from 1916 and the activities of the Licensing Reduction Board in shutting down street-corner pubs in inner working-class suburbs. Between 1910 and 1935 the Licensing Reduction Board closed more than two thousand hotels across Victoria, most of them either in the old gold towns or the inner suburbs of Melbourne.

To read more about Melbourne crime in the 1920's, click on the link below:

The business of ‘snow’ infiltrated Melbourne around 1923. ‘Snow’, or cocaine, was a hangover from WWI, where experiments in refining opiates for medical purposes produced the substance which was commonly used in dentistry and medicine of the era. “In 1923 shocked journalists discovered that the ‘snow habit’ had reached the slum areas of Melbourne”. The effects of ‘snow’, a “deleterious” substance, also confused police as they were different from the effects of alcohol and opium, both established abused substances.

Deals were sold for 2 shillings a packet, which made 3 lines or “sniffs”. The drugs came from dealers who purchased in bulk from chemists. With an increased thieving of chemist stores, ‘snow’ was even turning up at the racetrack, with horses being doped.

Having created solid racketeering and clean profit through the reliable cash flow of illegal liquor trading, established crooks explored the new trade of dealing narcotics. Unlike today where cocaine is synonymous with wealth, stardom and runny noses, ‘snow’ was associated with the worst cases of destitution, poverty and addiction affecting individuals and families within the inner suburbs of Melbourne.

Taken from Troublemag.com. (2015). STRALIAN STORIES: Snow Business – the thrills and kills of Squizzy Taylor | troublemag. [online] Available at: http://www.troublemag.com/stralian-stories-snow-business-the-thrills-and-kills-of-squizzy-taylor/ [Accessed 9 Jul. 2016].

This guide was prepared by Salam Caldis and Sue Patterson of Marymede College in Melbourne. Recreated here with permission and gratitude by Angus Pearson 2018.